Menu

It was 120 years ago, today

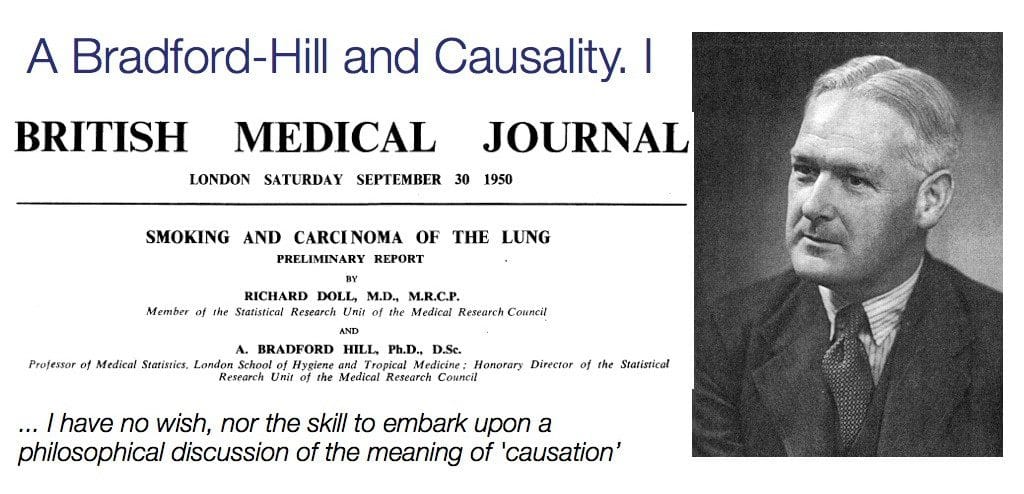

It was 120 years ago, todayWhen Austin Bradford Hill (8 July 1897 – 18 April 1991) was born in London. He was an English epidemiologist and statistician, pioneered the randomized clinical trial and, together with Richard Doll, demonstrated the connection between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Hill is widely known for pioneering the "Bradford Hill criteria" for determining a causal association; however, that seems to be a falsification from his personal views. He never seems to have seen these as 'criteria', yet merely 'viewpoints'.

As a child, he lived at the family home, Osborne House, Loughton, Essex; he was educated at Chigwell School, Essex, and later served as a pilot in the First World War but was invalided out when he contracted tuberculosis. Two years in hospital and two years of convalescence put a medical qualification out of the question and he took a degree in economics by correspondence at London University.

In 1922 Hill went to work for the Industry Fatigue Research Board. He was associated with the medical statistician Major Greenwood and, to improve his statistical knowledge, Hill attended lectures by Karl Pearson. When Greenwood accepted a chair at the newly formed London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Hill moved with him, becoming Reader in Epidemiology and Vital Statistics in 1933 and Professor of Medical Statistics in 1947.

Hill had a distinguished career in research and teaching and as author of a very successful textbook, Principles of Medical Statistics, but he is famous for two landmark studies. He was the statistician on the Medical Research Council Streptomycin in Tuberculosis Trials Committee and their study evaluating the use of streptomycin in treating tuberculosis, is generally accepted as the first randomised clinical trial. The use of randomisation in agricultural experiments had been pioneered by Ronald Aylmer Fisher. The second study was rather a series of studies with Richard Doll on smoking and lung cancer. The first paper, published in 1950, was a case-control study comparing lung cancer patients with matched controls. Doll and Hill also started a long-term prospective study of smoking and health. This was an investigation of the smoking habits and health of 40,701 British doctors for several years (British doctors study). Fisher was in profound disagreement with the conclusions and procedures of the smoking/cancer work and from 1957 he criticised the work in the press and in academic publications.

Hill was made a fellow of the Royal Society in 1954. Fisher was actually one of the proposers. The certificate of election read:

Has, by the application of statistical methods, made valuable contributions to our knowledge of the incidence and aetiology of industrial diseases, of the effects of internal migration upon mortality rates, and of the natural and experimental epidemiology of various infections, for example of the risks of an attack of poliomyelitis following inoculation procedures and of the risk of congenital abnormalities being precipitated by maternal rubella in the pregnant woman. Since the war he has demonstrated in an exact and controlled field survey the association between cigarette smoking and the incidence of cancer of the lung, and has been the leader in the development in medicine of the precise experimental methods now used nationally and internationally in the evaluation of new therapeutic and prophylactic agents.

In 1950–52 Hill was president of the Royal Statistical Society and was awarded its Guy Medal in Gold in 1953. He was knighted in 1961. On Hill's death Peter Armitage wrote,

"to anyone involved in medical statistics, epidemiology or public health, Bradford Hill was quite simply the world’s leading medical statistician."

Bradford Hill set out nine viewpoint on causality: strength of association, consistency, specificity, temporality, biological gradient, plausibility, coherence, experimental evidence, and analogy. While these viewpoints are helpful when considering cause and effect, he insisted that

“none of [his] nine viewpoints can bring indisputable evidence for or against the cause-and effect hypothesis”.

What they can do, with greater or lesser strength, is to help epidemiologists make up their minds on the fundamental question - Is there any other way of explaining the set of facts before them? Is there any other answer equally, or more, likely than cause and effect?

It is important to keep in mind that most judgments of cause in epidemiology are tentative and should remain open to change with new evidence. It is important to be remain critical, to aim always for stronger evidence, and to keep an open mind. Checklists of causal criteria should not replace critical thinking.

"The world is richer in associations than meanings, and it is the part of wisdom to differentiate the two."

John Barth, novelist.

References: